This article was originally posted in 2008

in tribute to Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990)

and also in memory of its author, Jeffrey Dane,

who was a researcher and author.

Jeffrey wrote extensively about composers and met several

who worked in Hollywood. He was a friend of composer, Miklos Rozsa,

about whom he wrote a book for the Rozsa centenary in 2007.

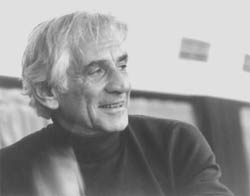

Leonard Bernstein: The Total Musician

A Personal Remembrance

by Jeffrey Dane

[photo by Pierre Voslinsky]

It was because of Leonard Bernstein that I chose to devote my life to music.I first met him during my student days, and though I never formally studied with him he was effectively a role-model for me during my formative years. My life would have taken a very different turn and I would not be the same person I am today if I hadn't known him and learned what I did: the value even of modest accomplishments (modest compared to his), and that it is possible to make a contribution, even if only an incremental one, to the sum of human knowledge and experience, and to one's chosen realm without being "the world's foremost authority" in it. This concept would surprise and has even disturbed some in academe, but it guides the independent historian in his or her work.

I acknowledge a marked tendency to form an almost emotional attachment to the composers (living or not) whose music I study, and I developed a genuine passion for the history, literature, composers and practitioners of the art. The responsibility for this fervor, which is still with me, falls to Leonard Bernstein.

The Conductor in Rehearsal

I attended countless rehearsals and performances of his, first at Carnegie Hall, then at Lincoln Center, and he invariably had a kind word of greeting for me. I was always struck by the simple human consideration he showed me on every one of the innumerable occasions on which I spoke with him. (The instances on which I met and spoke with Leopold Stokowski, "the Merlin of orchestral wizardry," were also very numerous, and while he was certainly cordial the character differences between the two men were as dissimilar as any two personalities could possibly be). With Bernstein, I found myself being treated with an unsolicited but sincere, personal kindness by a musician of immeasurable stature, one of the most important of our century. This kind of natural courtesy was relatively small and might seem insignificant -- but it was also genuine, and very much appreciated.

This is only one of those things about Leonard Bernstein I will not forget. I was a then-young student of music, completely unknown and obscure, and he had nothing to gain by treating me with such kindness. It was just indicative of the kind of man he was. Those who go about with their noses too high in the air have been known to trip over those who are "below" them -- but Mr. Bernstein was, simply put, a mensch (the German word for a real human being). It was very much to his credit that he was the warmest and most accessible among the many "Ivy League" people with whom I've come in contact. This is not a judgement of them, but an observation about him.

[Carnegie Hall in New York City, 1891]

My first in-person view of him was at a New York Philharmonic open rehearsal, when the orchestra still had its home at Carnegie Hall. I vividly recall not what I "expected" but what I didn't expect: to suddenly spot Leonard Bernstein leaving the wings, without official fanfare or announcement but amid an audible flurry of excitement in the audience, walking very casually toward the podium, dressed not in formal attire but in what appeared to be a grey T-shirt with long sleeves. All this seemed, then, somehow strange, but so do most first experiences.

Being rehearsed were Khachaturian's Piano Concerto (with 16-year-old Lorin Hollander as soloist), and Carlos Chavez' Sinfonia India. Only later on did I learn that this rehearsal shared many of the essential characteristics of Mr. Bernstein's Young People's Concerts: it was music-making at its highest level -- if not a thorough "education" (which takes years), then surely an in-depth, first-hand exposure to it, which can have enduring consequences. What I felt at that rehearsal made me resolve to have more of this, and that day's experiences had effects upon me

that have lasted to this very day.One morning soon afterward, I went not to school but to Carnegie Hall instead. In retrospect, it was a classic example of doing the wrong thing but for the right reasons: I was intent upon experiencing another rehearsal, and the possible consequences of my truancy from school mattered not. That I simply felt I "belonged" there might be what enabled me to just walk into the hall through the stage entrance with some of the other musicians. I was unquestioned by Carnegie personnel as I entered, but we must remember that the very early 1960s was a more innocent era. It was on this day that I had my first personal contact with Leonard Bernstein.

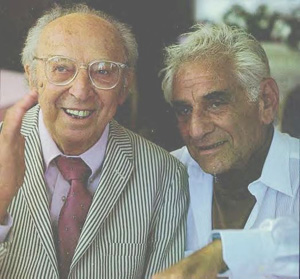

A symphony by David Diamond was being rehearsed. This was a working rehearsal so only a handful of people were there as listeners. After a few minutes, I turned around and saw, sitting a few rows behind me, David Diamond, another gentleman I didn't recognize (it was Marc Blitzstein), and the Dean of American Composers: Aaron Copland.

During the break, Mr. Bernstein leaped from the stage and walked up the center aisle to greet the three illustrious visitors. I soon approached them, merely to listen to (and hopefully learn from) their conversation. At that time I was frankly somewhat overwhelmed by being in their presence, and I impulsively said, "You know, I can't help feeling so insignificant standing among you gentlemen." Mr. Bernstein smiled at me and put his hand on my shoulder; Mr. Diamond looked puzzled; Mr. Blitzstein told me, "We're not monsters," and Aaron Copland looked at me, and with his iconic smile said, "Come join us!" I realized even at that tender and still impressionable age that his invitation was figurative, not literal -- but it was nevertheless very pleasant for me to be so treated by these significant figures in American music.

[Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein in the late 1980s]

Sammy Film Music Award for

Best Golden Age Film Score -- click here

Other Composer Tributes on this AMP website

For email contact -- click here

Please help support the educational mission of the

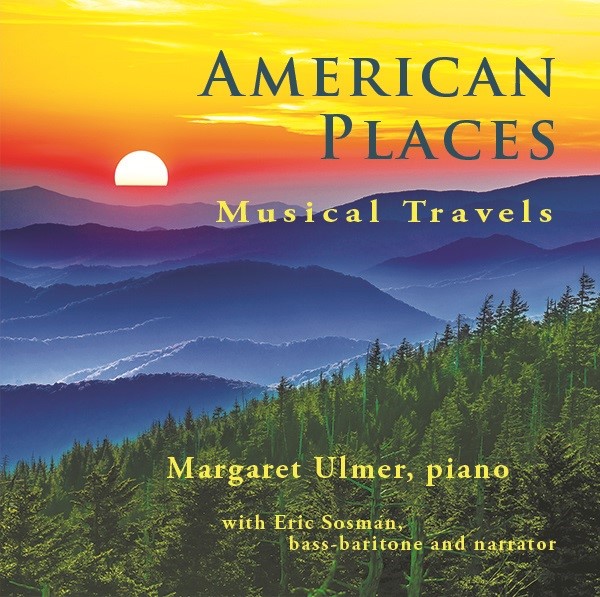

Order your copy of this limited edition CD

© 2008-2024 PineTree Productions. All Rights Reserved. Contact: pinetreepro@aol.com